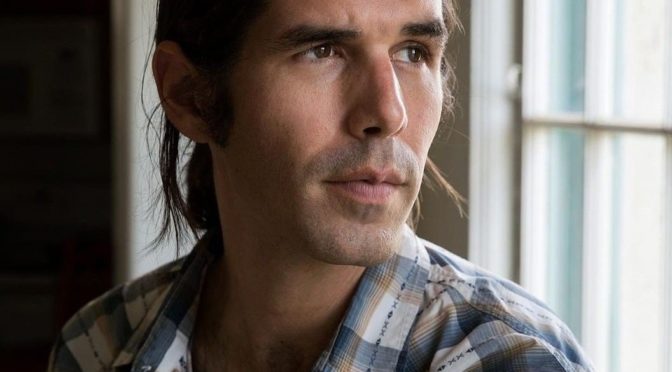

Beginning November 12th, Dr. Scott Warren will stand trial in Tucson Federal Court for a second time this year for offering food, water and beds to undocumented migrants in the borderlands. The charges against Dr. Warren are a marked escalation of an already deadly strategy of hyper-border militarization and prevention through deterrence. Join us in Tucson as we stand in solidarity with Dr. Warren and resist the criminalization of aid workers and border residents.

Continue reading RE-Trial Court SupportWater Not Walls: A Webinar with No More Deaths

Sunday, November 10th, 12 pst/1 mst/2 cst/3 est

On Sunday November 10th. We gave an overview of the legal challenges No More Deaths has faced this past year and discussed the re-trial of Dr. Scott Warren on federal harboring charges.

This webinar is designed to give participants the information and tools needed to speak about why the prosecution of aid workers sets a dangerous precedent for people of conscience everywhere.

We discussed the escalation of government targeting of aid workers here and abroad and what can be done to resist the criminalization of compassion.

Call for Mental Health and Wellness Practitioners

Call for Mental Health and Wellness Practitioners!

No More Deaths is seeking trauma-informed and -experienced mental-health professionals and wellness coaches/healers willing to provide no-cost or sliding-scale mental-health and holistic-health services to certain individuals affected by the humanitarian crisis on the Arizona border: namely, volunteers who provide humanitarian assistance to undocumented border crossers, refugees, recent immigrants, and their families.

Felony Trial Social Media Toolkit

— redirect —

Write an Op-Ed or Letter to the Editor

— redirect —

Analysis: Cartel scout cases show potential future of border-aid prosecutions

by Curt Prendergast Arizona Daily Star

The last two years saw a rash of criminal charges against border aid workers in Southern Arizona, raising questions about the future of humanitarian aid in a deadly border-crossing area.

A road map to that future may be found by looking back on how the U.S. Attorney’s Office went after cartel scouts and then expanded their pursuit to the variety of roles needed to support the scouts, according to an analysis of cases and trends in U.S. District Court in Tucson by the Arizona Daily Star.

As the U.S. Attorney’s Office pursued charges against nine volunteers with Tucson-based humanitarian aid group No More Deaths, prosecutors in Tucson also expanded the scope of cases involving cartel scouts.

Those scouts spend weeks on mountains west of Tucson and act as “air traffic controllers,” as one Border Patrol agent put it, for marijuana backpackers in the valleys below.

Prosecutors broke new legal ground in 2015 when a judge ruled a man working as a scout on a mountaintop near Ajo could be charged with conspiring to smuggle marijuana, despite not having any marijuana when he was arrested.

Since then, scout cases have grown to include scout “helpers” who cook and fetch supplies for scouts, drivers who drop off supplies, homeowners who store supplies, people buying groceries or wiring money to pay for supplies, and other roles.

If a jury were to convict Scott Warren, a volunteer with No More Deaths, at a retrial in November, he would be the first border aid worker convicted of felony human-smuggling charges in Tucson’s federal court in more than a decade.

Judging by what the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Arizona has done when breaking new legal ground with scout cases, any future trials of border aid workers potentially could see nurses, doctors, volunteers, or even donors to No More Deaths sitting at the defense table instead of in the courtroom gallery.

In the gallery

During Warren’s trial in June, Susannah Brown bowed her head and pinched the bridge of her nose as she sat in the gallery of a federal courtroom in Tucson.

A federal prosecutor was telling jurors that Brown, a 67-year-old nurse who works with humanitarian aid groups in Southern Arizona, conspired with Warren and others to smuggle two Central American men across the U.S.-Mexico border in January 2018 and help them get to Phoenix.

Brown regularly treats migrants for a number of ailments and injuries at a shelter in Sonoyta, the Mexican border town south of Ajo. She and her fellow volunteers also bring a truck with a big tank of water to the shelter, which has an unreliable hookup to the municipal water system.

In January 2018, Brown attended to the two Central American men at an aid station in Ajo, known as The Barn, and Dr. Norma Price gave a medical consultation by phone.

Prosecutors at Warren’s trial also said Irineo Mujica, the operator of the migrant shelter in Sonoyta, arranged to help the two Central Americans get to Ajo.

Brown, Price and Mujica were not charged with any offenses, but they remained in the crosshairs of the U.S. Attorney’s Office as Warren’s trial ended.

“So what the evidence shows in this case is that the defendant, Irineo Mujica, and Susannah Brown and the others conspired to further Kristian and Jose’s illegal journey into the United States,” federal prosecutor Anna Wright told the jurors in her closing arguments, according to a court transcript.

Wright also referred to two No More Deaths volunteers when she told jurors that in the days after the arrest, “at least two people intentionally went to The Barn and took things out, and they took those things out to help the defendant, and they handed those things over to the defendant.”

Rather than make money, Warren “gets to further the goals of the organization that he is a high-ranking leader in, and one of those goals, although never stated outright, is to thwart Border Patrol at every possible turn, to further the entry of illegal aliens,” Wright told jurors.

The Border Patrol also viewed No More Deaths as a smuggling organization, according to Agent John Marquez’s report detailing Warren’s arrest.

No More Deaths “was long suspected of illegally harboring and aiding illegal aliens and a search warrant for their illicit activities was recently executed at their humanitarian station near Arivaca, Arizona,” Marquez wrote.

He was referring to the raid of a No More Deaths camp near Arivaca in June 2017. Agents had followed the footprints of four people suspected of crossing the border illegally.

No volunteers were arrested, but they later said the raid and the surveillance that preceded it signaled a heightened level of tension between No More Deaths and the Border Patrol.

Warren’s trial ended with a mistrial after the jury split 8-4, favoring acquittal.

After more than a year of arguing that Warren was part of a conspiracy, prosecutors dropped the conspiracy charge when they announced in July their plan to retry Warren on harboring charges.

Circumstantial connections

Marijuana backpackers have trekked through the desert west of Tucson for many years, often led by scouts using binoculars and encrypted radios to keep the backpacking groups spread apart, as well as to let the groups know if Border Patrol agents were approaching.

Until 2015, prosecutors would charge scouts only with crossing the border illegally.

But a judge’s ruling in Tucson’s federal court in 2015, followed by two 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals decisions in 2017, opened the door for scouts to face conspiracy charges.

In the years that followed, prosecutors have charged at least 100 scouts with conspiring to smuggle marijuana, court records show.

As time went on, agents and prosecutors started targeting not only scouts, but the network of people who supported the scouts.

In one ongoing case, Border Patrol agents arrested Jose Angel Felix Ramirez, the suspected head scout for a drug-trafficking organization, in late 2017, and more than a dozen people accused of conspiring to smuggle loads of marijuana through the mountainous areas of the Tohono O’odham Nation.

In that case, agents arrested scouts and backpackers; helpers who picked up groceries, batteries and other supplies at the base of mountains; drivers who brought supplies to the mountains; a man who let the scouts use his house in a nearby village to store supplies; a woman in Phoenix who bought supplies; and a woman who loaned her car to supply drivers and paid people to buy supplies, according to plea agreements.

As prosecutors expanded the roles that could be included in the conspiracies, they also expanded how much marijuana a scout could be held responsible for conspiring to smuggle.

Initially, scouts were accused of conspiring to smuggle the equivalent of one backpack of marijuana. As time went on, prosecutors started accusing scouts of conspiring to smuggle all the marijuana backpacks that were caught in the scouts’ “view sheds,” or line of sight, while the scouts were on the mountain.

In the Felix case, members of the conspiracy were connected to about 4,300 pounds of marijuana, prosecutors said.

Humanitarian conspiracy?

Under the prosecution’s theory of Warren’s case, he acted as part of a criminal conspiracy.

That theory is in many ways analogous to theories put forth by prosecutors in scout cases.

From that prosecutorial line of thinking, if an aid volunteer cooked for a migrant who came into an aid station from the desert, how different would that be from helpers cooking for scouts on a mountaintop?

If a volunteer drove jugs of water, beans, socks, or gear to an aid station in Ajo or Arivaca, how different would that be from a person driving bags of food, batteries and gear to the base of a mountain where a scout worked?

If a Tucson resident donated money to No More Deaths to buy water and aid for migrants, how different would that be from people in Phoenix buying supplies for scouts?

If a volunteer said they had worked at an aid station for a week, could they be charged with aiding the illegal border crossings of however many migrants were caught in that area in the previous week?

U.S. Attorney Michael Bailey, who took the position in May, declined to be interviewed but issued a statement to the Star.

“Those who want only to give water to the thirsty should be commended,” Bailey said. “On the other hand, when one’s true goal is to assist an illegal immigrant in getting in without getting caught, such conduct is subject to prosecution.”

Nine No More Deaths volunteers, including Warren, were charged with misdemeanors related to leaving water and food on the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge in 2017. The charges included driving on unauthorized roads and abandoning property on the refuge.

The “bottom line” is that prosecutors could not convince a jury that Warren was guilty of any charges, said Paige Corich-Kleim, a No More Deaths volunteer.

“Prosecutors could try to cast a wide net, but they’d essentially be arguing that keeping people from dying is ‘furthering illegal presence,’ and I doubt any jury would agree with that,’ Corich-Kleim said.

Aid workers, Border Patrol agents, hunters and others in Southern Arizona have recovered nearly 3,000 sets of human remains believed to belong to migrants since 2001.

Andy Silverman, a law professor at the University of Arizona and a member of the No More Deaths legal team, said the difference between the scout cases and Warren’s case is that Warren was not involved in illegal activity.

“As they say, humanitarian aid is never a crime,” Silverman wrote in response to an inquiry from the Star.

“However, charging Scott and trying him for serious offenses — even though ultimately he should be found not guilty — has a chilling effect on people considering doing humanitarian work along the border,” Silverman wrote.

“But it will not stop such work,” he wrote. “Helping others in need has been part of our culture and the threat of criminal charges will not stop good folks from trying to save lives in our desert regions.”

Silverman said he would expect a “large public backlash” if prosecutors start charging all people who do humanitarian work.

“We have seen it in the Warren case and it would even be greater if the government starts to go after, for example, health professionals, shelter operators and others helping people in the deadly deserts along the border,” Silverman said.

A status conference in Warren’s case is scheduled for Monday, Aug. 5. His retrial is scheduled to start Nov. 12.

Legal Defense Outreach Program

UPDATE: Our legal defense community outreach program is now full. We are so grateful for all the interest and support, and you may be interested in our other volunteer opportunities. We also really appreciate opportunities to speak about the case, donations, shows of community support through yard signs in and around Tucson, and any help bringing awareness about the repression of migrants and the attempted criminalization of humanitarian aid to your communities.

Continue reading Legal Defense Outreach ProgramDOJ TO RETRY SCOTT WARREN ON HARBORING COUNTS

July 2nd, 2019, TUCSON, AZ – Prosecutors representing the United States government announced their intention to retry Scott Warren on two federal harboring charges, with an 8-day jury trial set for November 12, 2019 and dismissed the conspiracy count. If convicted on both harboring charges, Dr. Warren faces a sentence of up to ten years.

A hung jury failed to convict No More Deaths volunteer Scott Warren on June 11 on two counts of felony harboring and one count of felony conspiracy related to his humanitarian aid work in Ajo, Arizona.

Dr. Warren has received an outpouring of support from communities, elected officials, human rights defenders, and faith leaders across the globe. United Nations experts and fifteen US Senators urged the Department of Justice to drop charges against Dr. Warren, arguing that “providing humanitarian aid should never be a crime.”

Scott responded to this news with a statement:

Today the government decided to retry its case against me. We are ready for this second trial and more prepared than ever. However, I as well as most of you, remain unclear what the point of all this effort, time, and money has been. It has been deeply exhausting and troublesome to my friends and family and loved ones. But we have all done our best and we really should take a moment to celebrate that as we prepare for the future.

While I do not know what the government has hoped to accomplish here I do know what the effect of all this has been. A raising of public consciousness. A greater awareness of the humanitarian crisis in the borderland. More volunteers who want to stand in solidarity with migrants. Local residents stiffened in their resistance to border walls and the militarization of our communities. And a flood of water into the desert at a time when it is most needed.

Thank you for all of your support and I love you all very much.

Now Hiring: Media Coordinator

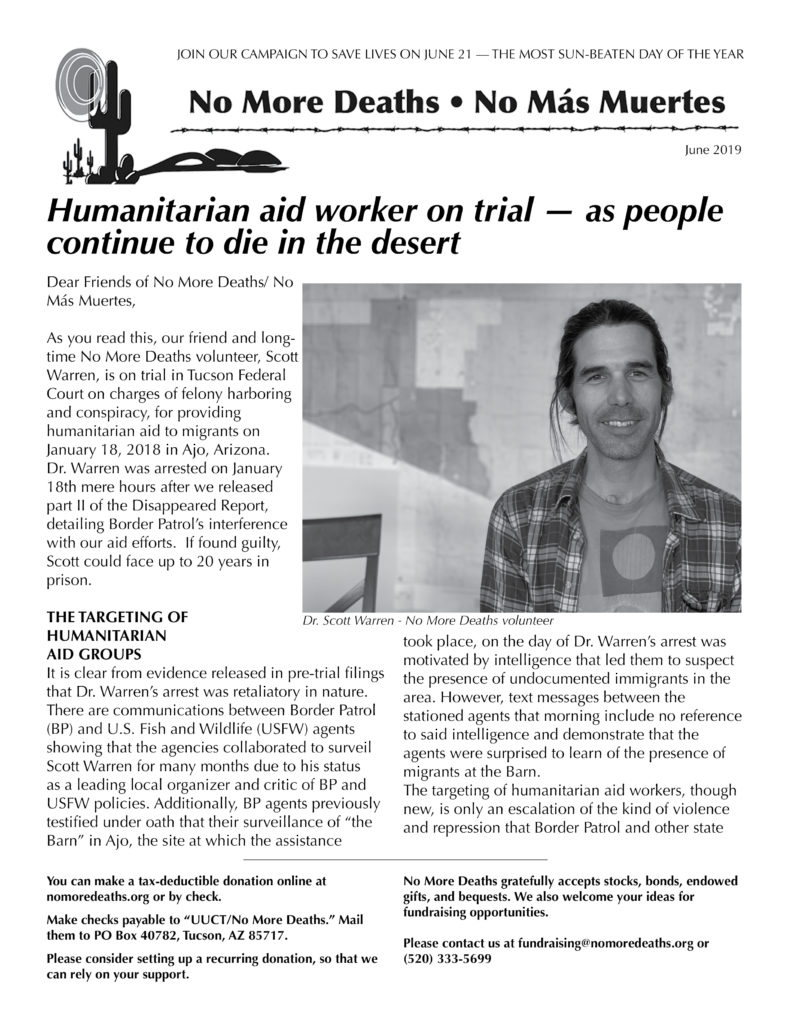

Newsletter June 2019

Here is our summer newsletter! Click to download.