This article by Dorothy Chao appears in our fall newsletter. Chao attended the July 20, 2015 sentencing of 12 local people (some of them No More Deaths volunteers) who chained themselves to the wheels of two buses carrying undocumented migrants to federal court in Tucson on October 11, 2013. The protesters stopped federal marshals from taking the group to Operation Streamline, a fast-track proceeding that sentences migrants to prison for illegal entry. In March, Pima County Justice Court Judge Susan Bacal found the defendants guilty of obstructing a highway and creating a public nuisance.

I am crowded into this Tucson courtroom with images in my head from my morning spent in Nogales, Sonora, working as a No More Deaths (NMD) volunteer with recently deported people. The distressed faces of people I met in Nogales this morning who went through Streamline and spent time in jail are here in the courtroom with me.

The courtroom is packed; the air charged. Twelve of the defendants are facing sentencing today; potentially 150 hours of community service each. They stopped two buses of migrants on the I-10 access road here in Tucson and chained themselves around the buses’ gigantic wheels. The buses carried randomly selected migrants who would have been tried “en masse” in Operation Streamline court. They would have faced criminal charges for illegal entry and sentenced to a few months to a few years of prison time.

One after another we hear their testimonies. Every one of them is committed in their daily lives to doing volunteer work to help ameliorate the suffering caused by our broken immigration policy.

Listening to the defendants’ individual testimonies, I am struck by how totally committed these people are to their personal moral values and to being advocates for justice. They put their bodies in physical harm’s way. Beyond that, they could have faced jail time and felony charges with all the associated stigma, disenfranchisement, and loss of personal freedom.

One after another we hear their testimonies. They are school teachers, health care professionals, members of nonprofit boards, and former government professionals. Every one of them is committed in their daily lives to doing volunteer work to help ameliorate the suffering caused by our broken US immigration policy.

I want to share what I heard in the courtroom that day from three of the defendants. Steve Johnston spoke about the deaths he has witnessed in the desert; he had trouble speaking and frequently broke down as he relived each memory. Dévora Gonzales, holding her newborn close, stated how the birth of her baby served to recommit her to doing everything she could for family unity.

Paula McPheeters was absolutely stunning and straight to the point: “I am a retired Tucson school teacher,” she said, “and I saw the terrible effects of losing a family member on my students every day.” The collective testimony was quite an indictment of Operation Streamline and everything it represents. Many in the courtroom, including myself, were in tears.

How exciting to be in the courtroom when it erupted with pleasure when the judge granted “time served”!

Margo Cowan, serving as defense attorney, summed things up in her closing statement. She pointed out that it was the city police who decided to close both lanes of traffic (by the buses) instead of just one, and that the people of Tucson put up with traffic rerouting for unknown reasons every day. She commented on the overwhelming amount of community service each of the defendants do every day of their own free will.

How exciting to be in the courtroom when it erupted with pleasure when the judge granted “time served”! (The 14 hours the defendants spent in jail after their arrests.)

I am reminded of why I decided to move to Tucson four years ago. I am honored to live here and be a part of this wonderful activist community, to have a working link to these people through NMD and call them my friends!

In their own words—excerpts from statements by NMD defendants

I took action on October 11, 2013 because I couldn’t handle the frustration and pain I feel every time I tell a mother with babies next to her that, in all likelihood, nothing can be done … Something must be done … to work toward stopping mass criminalization, mass deportation and mass incarceration … Prior to that day, most of the country had never heard of Operation Streamline … I did what I did in the hope that many more people would become familiar with the anguish felt by families like Amy’s, and take meaningful action to right those wrongs … I pray that the actions that we are being sentenced for today have made some difference toward that end, and will contribute ultimately to correcting a terrible wrong that is being committed, every single day, by our government.—Sarah Launius

I think of my mom, María Jesús, who’s here in the courtroom today. You came to the US as a child—luckily made it across, got naturalized citizenship later as a young adult, built a family. I and my siblings were born here. But, under different circumstances, I know it could have been you on that bus. So, with that in mind, I locked myself down around that bus’s tire and didn’t let go even when police ordered me to do so under threat of arrest. I think of my cousin Carla who was living with us … when I was a child. And then one day she was gone. She had been deported. All she wanted to do here was work, start a family … and then our immigration-enforcement system took it all away. Her daughter and father of her children are still here while she lives separated from them in Mexico with her other child … Now the consequences are unimaginably worse on families whose members’ lives are ruined by these unjust criminal records and jail sentences.—Gabe Schivone

Streamline tries to grind down people’s hopes and dreams of return … The US Sentencing Commission recently reported that about 50 percent of immigrant re-entry offenders have children living in the US. They all said the word culpable or guilty while shackled in front of a judge with no due process and little understanding of how that could forever ruin their chances of legalizing their status … I locked myself under the bus as a true expression of my faith. I believe in a God of radical love and inclusion who sets the captives free. Operation Streamline is a modern-day slave trade steeped with racism, selling shackled migrants to fill the beds of private prisons for 30, 60, 180 days, and years if caught again. My conduct that day may have been a “public nuisance,” but for that day it prevented an unethical and unjust harm to 70 people on those buses. With these charges, now I’ll be a criminal too, but in solidarity with my heroes.—Maryada Vallet

Why did I crawl under the Streamline bus on October 11, 2013? For my close friends, the Huerta/Ortiz/Pérez family, who immigrated to Tucson from Mexico in 1991 … Carlos Omar Pérez was arrested illegally “driving while brown” in a white neighborhood, turned over to Border Patrol and ultimately deported … A more valuable citizen we could not have, but he’s barred from entry into the US for 10 years … Why? In memory of Beatriz Adriana Sánchez Salazar, 23, who died of hyperthermia in the mountains south of Ruby Road on July 4, 2005, during my first week with No More Deaths … Why? For José, 25 years in Phoenix working as a stonemason, arrested and deported for running a stop sign on his bicycle, who we luckily found semiconscious and near death under a juniper in a wash away from any trail … The worldwide civil-rights movement of the 21st century is represented right here by the cruelty of Operation Streamline and a border policy of deterrence based on imprisonment and death.—Steve Johnston

Read next story:

Nogales project evolves to aid dispossessed migrants

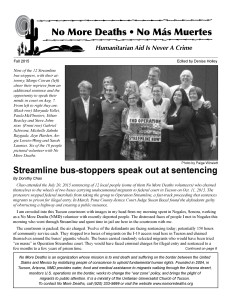

Featured photo: Nine of the 12 Streamline bus stoppers, with their attorney Margo Cowan (left), cheer their reprieve from an additional sentence and the opportunity to speak their minds in court on August 7. From left to right they are: (back row) Maryada Vallet, Paula McPheeters, Ethan Beasley and Steve Johnston; (front row) Gabriel Schivone, Michelle Jahnke Raygada, Jaye Harden, Angie Loreto-Wong and Sarah Launius. Six of the 10 people pictured volunteer with No More Deaths. Photo by Paige Winslett.